American pragmatism

pp. 174-203

in: , Twentieth-century Western philosophy of religion 1900–2000, Berlin, Springer, 2000Abstract

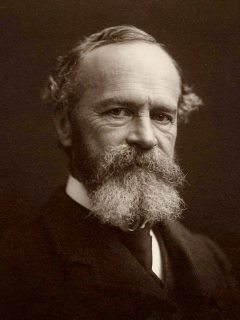

During the academic year, 1901/1902, William James delivered the Gifford Lectures at the University of Edinburgh. A year earlier, Josiah Royce had commented to James after delivering his own Gifford Lectures, "Everywhere they ask about you, and regard me only as the advance agent of the true American theory. That they await from you."1 This new theory came to be known as pragmatism. Although it has its European analogues, it is for the most part an American movement that had its beginnings in the meetings of the Metaphysical Club at Harvard University during the 1870s. James considered Charles Sanders Peirce the founder of pragmatism, and they along with John Dewey are the major representatives of the tradition. Although Peirce, James and Dewey differ in many ways, they agree in rejecting the claim that one should accept as meaningful and true only what conforms to the dictates of reason, and in bringing thought and action into a close relationship. In his well known article, "How to Make Our Ideas Clear," Peirce presents pragmatism as a method or procedure for determining the empirically significant meaning of our ideas. The whole purpose of thought, he argues, is to produce habits of action. Thus, to develop the meaning of a thought we have "simply to determine what habits it produces, for what a thing means is simply what habit it involves."2Every distinction of thought comes down to what is tangible and conceivably practical. "What the habit is depends on when and how it causes us to act. As for when, every stimulus to action is derived from perception; as for how, every purpose of action is to produce some sensible action."3